What will happen when "Intelligence" is no longer a limiting resource? Does it end cyclicality for chips and energy? Why compute demand might increase 12,700% over the next 10 years

I’ve been noticing how similar I am to an LLM lately. If you ask me something about a topic I will happily engage and share my thoughts at length. However, when I go into Deep Research mode I frequently find myself deciding that I do not in fact even know what I think about most things (to the extent I’d be willing to wager $ on them around some outcome, for example) - and it really takes sitting down and writing about them for me to “learn what I actually think”. One of the things I spend the most time thinking about these days is the answer to the question: how much compute will we need in 5 or 10 years?

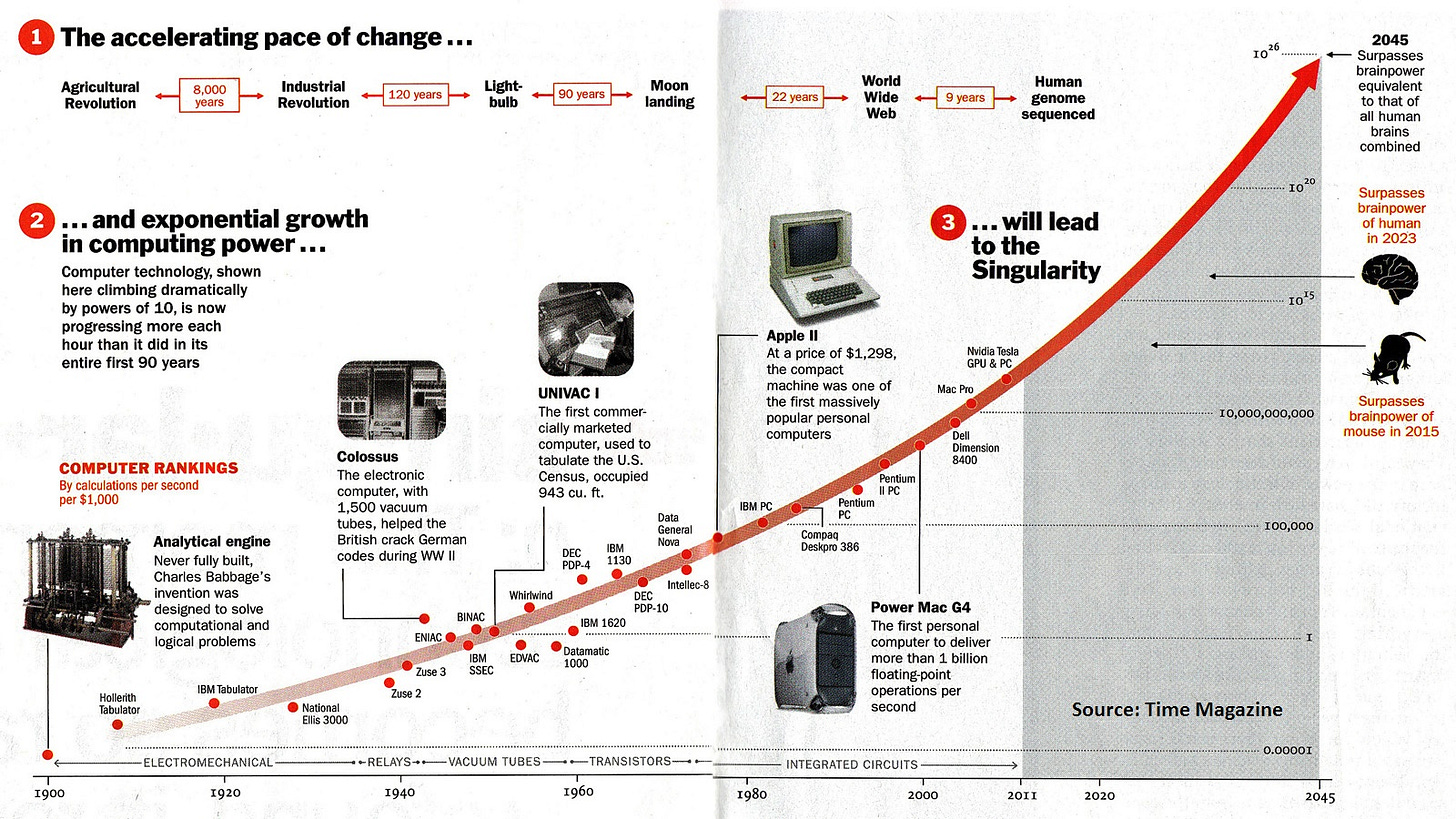

Consider how remarkably accurate Ray Kurzweil’s predictions of future compute capabilities (both demand and power per $) have been.

Decades ago he predicted 2023 would be the year when widely available computers would be capable of human level cognition. Given the capabilities of LLMs today that seems pretty remarkable. 2023 is unquestionably the year that machines felt like they “woke up” via mastering human language.

One of my predictions that has panned out accurately is that the end of Moore’s law wouldn’t slow anything down - and that the pace of technological advance would continue to accelerate despite the slowing rate at which we can fit more transistors on a chip.

I did not predict Nvidia’s relevance to AI nor did I predict that AI/ML would collectively lead to the greatest capex cycle in history. I didn’t predict the insane improvement from Hopper to Blackwell to Rubin (omg, nuts, read the latest Semianalysis piece linked here). But - what I did was extrapolate - as Kurzweil has - a trend that has been in place for a very long time (see this post for the deep dive on “The Exponential Growth of Progress”.

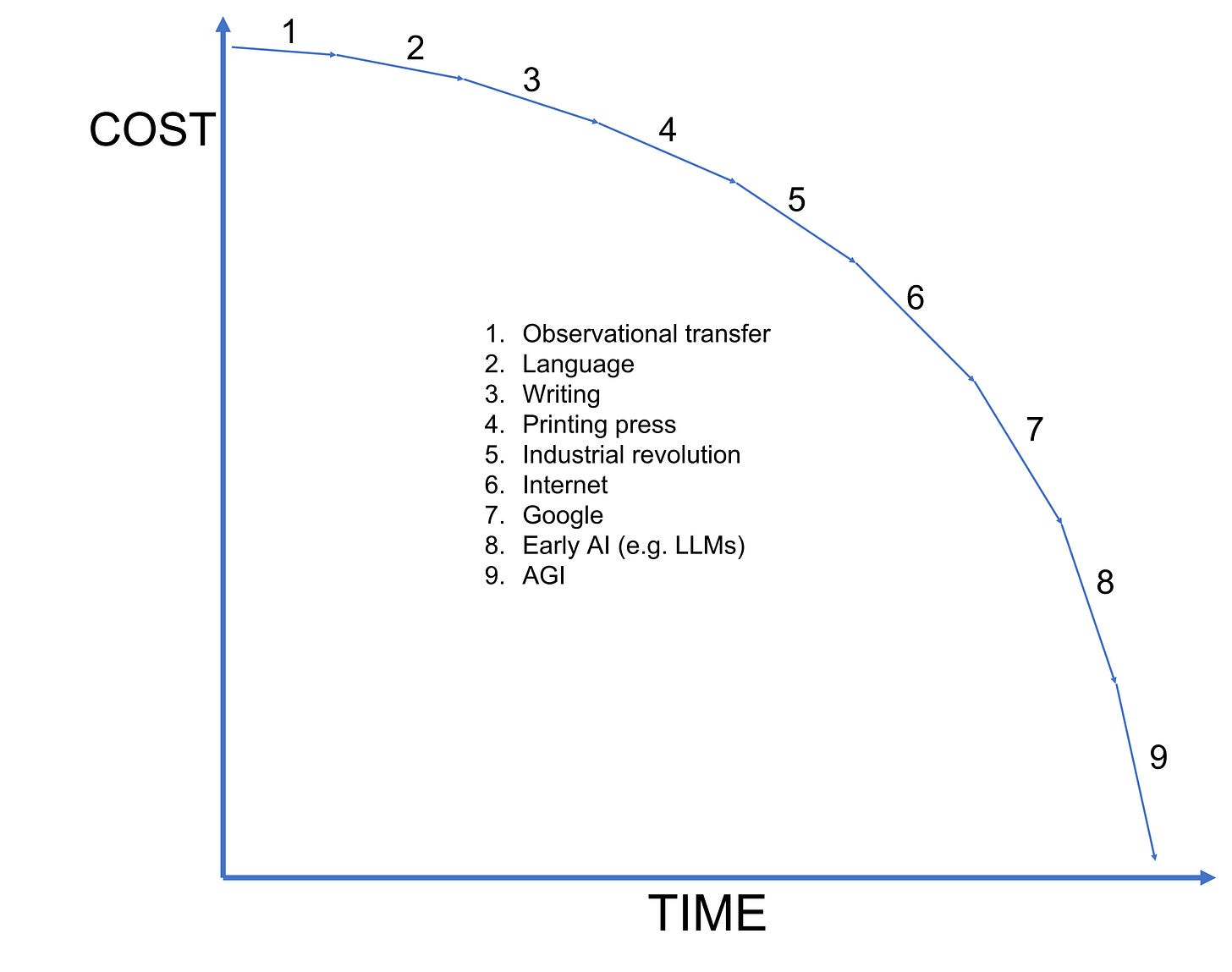

In the above post I commented that for most of history (4.4 billion years) progress - which I define as “information growth” - was driven by evolution. For example, two pterodactyls contain more information than one, but adding a new species via evolution- a velociraptor for example - does far more to increase total information than adding even another 10 pterodactyls.

All information growth was caused by evolution until humans came along. Humans were able to spread information from one to another through advanced communication + memory. For a few hundred thousand years humans were the dominant cause of information growth. Then we started to invent tools. Tools are anything useful insofar as increasing total information. Language is a tool. Computers are a tool. Farming techniques are a tool. Over time the contribution (“Market Share”) of tools to information growth has increased.

Crucially, for 99.999999% of the past 4 billion years (since the first anaerobic bacteria started multiplying) intelligence has been the limiting factor for progress:

If you want to do a gut check about when tools became more important to progress than human (“labor”) - I’d say to contemplate when the nerds started to take over. Today they account for the vast majority of new wealth creation (Musk, Zuck, Bezos, etc).

Nerds leverage the value of tools far better than do other humans - Elon being the preeminent example. Moving on, what has happened over the past 30 years is that tools became far more impactful to progress than labor. 50 years ago tools might have been +/- 10 points, but today they are obviously dominant. Consider how common it is to have companies with 100,000 employees that are worth more than the bottom 3 billion people on Earth put together. Similarly, consider how increasingly common it is to have individuals running businesses that make $1-10m per year? I see a new example pop up almost daily.

For the first time ever - thanks to AI - progress will not be [human intelligence] constrained. I think this happens within the next 10 years, and will obviously be the case post 2035.

The ramifications of this are profound. Let’s unpack it.

I need to clarify that when I say “natural resources” will be the limiting factor - I mean our ability to extract them from the earth and sky. I also want to stress that so far we don’t have a resource extraction problem - we have a red tape problem. China for example is able to build energy infrastructure at a rate - literally - 10X faster than we can. The bottlenecks we have in the United States around building more energy (whether it be nuclear or natural gas or the transformers needed to take energy from the grid and put it into a data center) are entirely self-inflicted. But I think this changes eventually and it simply won’t be physically possible to build all of the energy we want to use (until the physical robots start making new physical robots - analogous to digital intelligence that is recursively self-improving).

The price of resources (e.g. natural gas) are set through a combination of supply and demand. Historically, demand for commodities has always fluctuated wildly - that’s why we call them “cyclicals”. Prices fluctuate because demand increases - so the price goes up - so more projects to extract more of the resource become economically justified - so capacity increases - then capacity overshoots and price comes down again. A tale as old as time.

Here’s the thing - I posit that the reason capacity overshoots is because intelligence has been a “limiting resource”. Capacity overshoots because we don’t come up with a new source of demand before the old source of demand S curves. We have something like the following:

The reason price comes down is because we don’t get a new S curve to take place of the one before it (or more realistically, we don’t get many new S curves to take place of the many burning out):

I’ve overlayed what I expect to happen to cyclical capex (both for chips and natural resources) on top of Ray Kurzweil’s chart of the intelligence explosion:

I think we’re already seeing cycles shrink in terms of both [peak-trough amplitude] and frequency. While the cycle has always been following this trend of up and to the right - might we eventually just get to a point where the cycles are barely noticeable if at all?

When people talk about a “Fast Takeoff” - what they’re referring to is intelligence that becomes capable of improving itself. It can update its code, make itself more energy efficient, make itself smarter, etc. Another term for this is recursive self-improvement. Recursive self-improvement is what will effectively once and for all drive the cost of intelligence asymptotically to zero. I made this chart for a different post and it plots the cost of intelligence against time.

In economics there is a concept called price elasticity. It describes how changes in price impact demand. Some goods are completely inelastic - it doesn’t matter what the price is no one will change their purchasing habits. An example of a good with zero price elasticity is my brother’s dog’s shit. It has zero value no matter what price it is because the demand for it is zero.

At the exact opposite end of the spectrum is a patriot missile. The government will pay whatever it costs to purchase one, regardless of price.

A typical price elasticity chart as used in college textbooks looks something like the following.

The chart is a tad misleading because it seems to imply that the demand for goods will go near infinity long before price hits zero, but you get the gist.

In the real world demand for everything is limited. There’s only so much humans can use. But again - I posit this is due to intelligence being a limiting resource. Consider the following:

The most price-elastic good imaginable - where reducing the price toward zero would theoretically drive demand toward infinity - is something with:

No inherent consumption limits

Universal desirability

Minimal storage or usage costs

A classic theoretical example is money itself, or something extremely close to it, like risk-free financial assets (e.g. Treasury bills). If you were to offer money at a discount (selling a dollar for less than a dollar), rationally, everyone would infinitely demand it.

Another clear example could be Energy (e.g. electricity). If energy were truly free and limitless, people would immediately find infinite ways to use it, such as cryptocurrency mining, artificial intelligence computation, climate control, desalination, vertical farming, or large-scale data centers. As the cost approaches zero, the demand could theoretically spike indefinitely, limited only by physical constraints, not desirability.

Artificial Intelligence that has human-level agency (which is my definition of AGI) also deserves a spot on this list. Why?

Infinite usefulness.

It will enhance productivity, problem-solving, and innovation across every human activity. It will also come up with the solution to rendering humans “pointless” insofar as economic productivity goes.

There’s no upper bound tot he utility of increased intelligence - every increment unlocks additional possibilities, compounding its desirability.

Universal Demand.

Every individual, business, government or institution will want as much as they can get their hands on - particularly once intelligence becomes embodied

Unlike niche products, intelligence has applicability across all fields, from medicine and education to finance and engineering to companionship

Near-zero Marginal Cost

Software-based AGI could potentially scale with very low marginal costs - duplicating intelligence is far cheaper than replicating physical commodities

If the price approaches zero, the lack of meaningful constraints on distribution (let’s go open source!!!) could drive exponential demand

Accelerating Returns

AGI amplifies itself (recursively self-improving). This creates a snowball effect.

More intelligence = more value creation = more resources to invest in further intelligence.

Intuitively this feels right, but let’s get tangible

It’s one thing to predict that demand for intelligence will be infinite. Most people probably agree that if energy and intelligence were free demand would be infinite. What savvy people wonder is whether the cycles are really going to shrink in amplitude and frequency.

Very smart people are worried that we are in an AI bubble - Nvidia will not hit its long term revenue targets - the Big Tech capex boom is unsustainable, etc. My view on this is that I don’t know, and to borrow a wimpy prediction from Larry Summers (recently forecasted the likelihood of recession was 50/50) - I feel the same about whether we’ll see another cycle.

What seems obvious to me is that if we get digital AGI then intelligence is no longer a limitation - therefore the only limitation is our ability to marshal physical resources - therefore any parts of the physical resource supply chain that can’t keep up with demand will stop experiencing price cyclicality.

Note that we could (and will!) still see cyclicality within the ecosystem. For example - maybe we’re able to extract oil or build solar panels faster than we can build transformers. If this is the case and transformers become the bottleneck, then prices for solar panels and oil could still fall if we have tons of production that can’t be put to use. The same could be true about the cyclicality of transformer prices if we are able to scale production of them far faster than the energy required to make them useful. But, these could be thought of as “mini-cycles” within the broader cyclicality of energy demand. What seems obvious is that when intelligence is no longer a limitation the cyclicality of energy demand itself will end.

What about chip demand? Interestingly, I think we end up in the same place post-AGI. The cyclicality in demand for semiconductors will end, but within the ecosystem bottlenecks could occur in semiconductor capital equipment, energy production, data center construction, etc. What will change is that the mega-cycles around demand for “intelligence” (e.g. semiconductors) will end.

One implication of not having what I’ll call “macro cycles” is that we can expect capex booms and busts to be smaller in the future (when aggregated). The busts in one area will be counter-balanced by the booms in another area - for example a bust in E&P (exploration and production) might be accompanied by a boom in expanding the grid. Similarly, a “bust” in logic/GPU chips might be accompanied by a boom in demand for memory and analog.

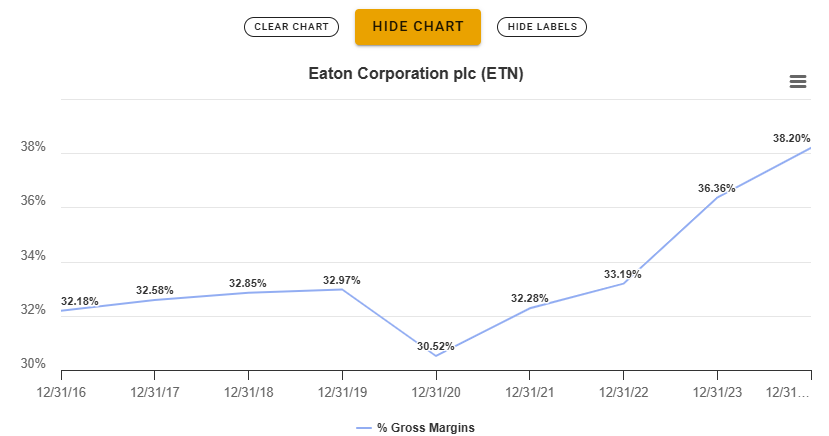

There is another implication which I think is more actionable - and that is the margins of the basket should increase over time. Let me explain.

Predicting the future is tough, but it is far easier to predict micro than macro. If the macro is guaranteed (e.g. increased demand for energy at a rate > production can expand) then what executives really need to be able to forecast is how long it will take a given bottleneck (a “micro”) to get resolved.

Obviously the macro is not precisely forecastable, but it is more forecastable than it has ever been in the past (and will become reasonably forecastable once we get AGI). Less variables impacting future demand make it easier for businesses to plan which in turn makes it easier to improve margins.

There is also another factor which seems to already be in play. The people who want more energy have a higher and better use for it than everyone who came before. Nvidia’s margins are what they are because the people buying their chips perceive them as having enormous potential value. Big Tech feels similarly about the value of data centers. The cost of Nvidia’s chips and the cost to construct a data center are - so far - perceived as being small relative to the potential upside.

Quick aside: I’d argue that Meta has already proven sustainable high ROI on their Nvidia spend.

Hence the improving margins of companies like Sterling Infrastructure and Eaton:

Again - maybe we’re overbuilding now, I don’t know. But, what I do know is that AGI is a sufficiently “high and good” use case that much higher margins will be supported across the ecosystem of companies enabling its proliferation.

My expectation moving forward is that margins will rise for all companies, and they’ll rise more quickly for companies in the United States than elsewhere due primarily to looser labor laws - American companies can basically fire at will - this is not true in ANY OTHER major economic zone.

To sum it up, I expect cyclicality to decrease at the same time as margins are increasing. The margin increases will be larger in percent terms for the companies who are moving to a less-cyclical future. The net result of less cyclicality and higher margins is that valuations should increase over time.

I went back and read this post from the start until this point and thought of better ways to organize and present these thoughts, alas I don’t have infinite time and I’d rather get more thoughts on paper than improve the presentation of what I’ve got so far. Also, back to my comment about feeling like an LLM lately - this post is sort of like that. I just started writing and went till I finished - analogous to the LLM doing some “thinking” in the background - except instead of doing the final edit I’m just publishing the thinking part.

Now back to the post.

Exponentials on top of exponentials

I’m not going to go through the work or address these topics in detail b/c this post is getting long enough, but I wanted to mention another thing I’ve spent a ton of time thinking about: how much data will we be using in ten years - and how will that usage break down?

In 2006 an average “techie” with a fast internet connection probably used around 25GB of data per month.

I just looked up how much I use per month and it’s ~1,600GB.

That represents a 6,300% increase over ~20 years.

It seems reasonable to me that the average increase over the next 10 years will be twice as much as it was collectively over the past 20 years (this actually feels extremely conservative). Meaning, we’ll have a ~12,700% increase in the amount of data a person is using per month.

This equates to 204 Terabytes per month or almost 7 per day.

For reference and just to get your mental juices flowing - most data consumed on the internet 20 years ago was peer to peer file sharing. Post smartphones it became content related - creating, viewing, delivering, etc + the compute spent on ML to turn that content into signal for purposes of serving ads.

Interestingly, the biggest source of data usage for me is Twitter (specifically on my phone). At first I thought this was strange because I never watch videos on Twitter (or rarely). How could Twitter be using more data than YouTube - which I am constantly streaming and spend more time using? What gives?

Agentic AI = more compute

I realized what’s happening is that Twitter is regularly caching content so that it’s easily accessible without needing to load. The reason this is interesting to me is because the number one use of data in the future will be - imho - personalized agents caching data so that they can talk to us about that data with zero latency - like in “Her”.

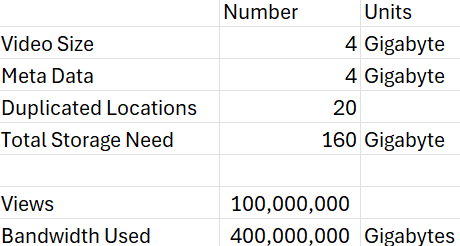

Let me explain. Today if someone uploads a video to YouTube that video generates data every time it is streamed to a person. For example: 100 million views of a 4GB video = 400 million GB of data streamed. Further, the video data is probably stored in 15-20 data centers around the world. Each video will on average also have meta-data stored (makes AI be able to understand it, used to serve ads optimized around it, etc) that is greater than the video size itself. So for this example we have the following:

Now - in order for “Her” to become a reality (and it will, likely around 2028 because the market TAM for Her is many trillions and 2028 is when hardware should be getting close to being able to handle it on a mobile device) - she has to be able to communicate with us with zero latency. That means lots of caching needs to be done - either on device or in a “cloud” that has a more limited search space - maybe a “personal cloud”.

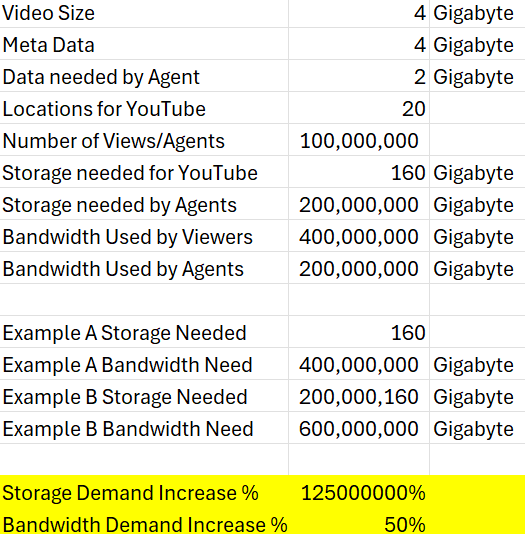

Literally everything we come in contact with - what we purchase, who we talked to recently, what movies we’ve watched, what we’re working on - everything. The AI will essentially need to continuously predict what we’re most likely to inquire about - and then have that information at the ready so it doesn’t have to spend an awkward amount of time seeking it out before responding to an inquiry about it. This will require enormous amounts of dynamic caching. In order for the AI to talk to us about the movie - for example - it will likely need to have cached a significant portion of the meta data. We might end up with something like the following…

Note bandwidth demand increases by 50%, but storage demand increases by 125,000,000% (125 million percent). Each agent needs to have its own copy of the meta data. Now - I’m sure in practice the percent increase in demand for storage will be lower b/c as demand grows novel solutions will be found to lower the cost of delivery. But how much will demand for memory grow? 1 order of magnitude over 10 years? 2? 3?

And this is just one of many examples I can think of that could cause demand for compute / chips to skyrocket.

“Thinking AI” = more compute

Jensen commented at GTC on Tuesday that inference demand moving forward will be 100X+ greater than Nvidia had thought it would be at this time last year. Why? Because LLMs last year were just taking a single crack at coming up with an answer to a problem. Now they are “deep thinking”. The thinking part is generating on average 100X the number of tokens per question (you don’t see all of the tokens it generates, just the ones that are distilled into the final answer). I gut checked this with ChatGPT and Grok - testing out the difference in time to respond - and it passes the sniff test.

When stocks moon like Nvidia has lately - most people think that the “bold” prediction is that it will keep mooning. Statistically speaking this is incorrect. The bold prediction is never that the trend will continue - that is the “expected case”. When stocks run far longer than anyone expects it is because expectations don’t keep up with reality. This is why Apple didn’t go up 1000% in a day when it released the iPhone - instead it compounded at 20%+ spread out pretty evenly over the next 15 years. I am not making a prediction about where Nvidia will go - just pointing out that the odds are always - statistically speaking - in favor of a trend continuing. Note this is NOT the same as predicting a continuing trend for a company like Gamestop which has deteriorating fundamentals and no growth. There is a fundamental limit to the price people are willing to pay for an asset that has no ability to create demand for itself (by using profits to repurchase shares).

There is no such limit for companies who can create their own demand using profits. Nvidia’s forward PE is 25, lower than it has been since its 10X run started - because profits have increased faster than its share price.

I’m going to stop the post with a list of things for you to think about if you want to try and wrap your head around how much compute we’re going to need in the future:

Frontier AI model training

Inference scaling - particularly when Agents are asking Agents to do things

Synthetic data generation and digital simulations

Cybersecurity (imagine 1 billion agents trying to hack things all the time 24/7 - the best way to try and defend against something like that would be to have 10 billion “good agents” doing the same thing and identifying bugs faster)

Real-time rendering for augmented reality

Autonomous robots (vehicles, drones, humanoids, etc)

HPC / Scientific simulations (weather prediction)

Edge computing and proliferation of IoT devices

Space-based sensing and earth observation data

One final closing thought - in a world where resources become extremely cheap we can do things like stop hurricanes in their tracks. How? Imagine you have 1,000 giant ships with Cones on them. They ride around the outside of the hurricane and use the cones to funnel the wind power into on-board energy, simultaneously sucking the energy out of the hurricane. The problem is these ships are too expensive to build today - but they won’t be tomorrow!

The future is going to be wild. It’s coming so fast. Get pumped, stay healthy, investigate deep ketosis.

-Ben

💯✅